The dysfunctional relationship food companies have with consumers, insurance providers have with those being covered, and investment companies have with their investors are remarkably similar. I suppose similar conclusions could be drawn about business in general: there is often a great mismatch of interests between buyers and sellers. Unless acting in the best interest of a client will increase profits, clever and often deceptive marketing strategies aimed at maximizing sales will be practiced, at the expense of the consumer. In economics a similar concept is known as a "moral hazard." (Not entirely unrelated, this last weekend I couldn't help but watch in fascination as a California Highway Patrolman hid patiently behind a sign with his radar gun, waiting for an unsuspecting speeder to pass. Both he and I were hoping for a violator: it would have fulfilled the cop's quota, and provided me with a bit of sadistic entertainment. My point: praying for a speeding driver is not in the best interest of anyone.)

Just this week, Michael

Pollan discussed a scenario in which this could change, as a result of the food industry and the insurance industry becoming at odds over American's health. The argument is actually quite intriguing. Currently, the U.S. industrial food system produces lots of cheap, high-calorie foods, and as a result,

Americans are getting fatter and sicker. If health care reform prohibits insurance companies from charging more to "higher risk" persons, and simultaneously requires coverage to sick individuals, then it is in the insurance industry's best interest to push the food industry to change it's ways. On this blog, I have often said that the food system and our national health are inextricably linked, so it will be interesting to see how this actually plays out.

When not pushing to reform the multi-trillion dollar

health care system, President Obama has been pursuing other equally lofty goals. Today, on the one-year anniversary of Lehman Brothers' collapse, he was on Wall Street, touting the need to

reform of the financial system as well. His speech primarily addressed the need to prevent further financial meltdowns by forcing institutions to act more responsibly, through the creation of a Consumer Financial Protection Agency. A major focus of overhaul would be the financial derivatives market.

The moral hazard associated with redistributing risk, through the creation and sale of derivative securities, was a major component of the Great Recession. In my current profession, I spend a good deal of time discussing the underlying models and pricing methodologies for fixed income derivatives. I'm not exactly a financial engineer, but I act as a "translator" of sorts, explaining various models with names such as the Black-Scholes option pricing model (which I puckishly call the "B.S." model), the 2-Factor Gaussian Copula, the Hull-White version of the Linear Gaussian Model, Jump Diffusion Option-Adjusted Spread, and the "Stochastic Alpha Beta Rho" model, otherwise known as SABR ("Saber"). Got that? Good. Now give us your life's savings and we'll put it to work.

The most famous of these models, the Black-Scholes model, requires some major assumptions to be "relaxed" in order to make it spit out reasonable answers. It assumes that volatility, or the financial world's way of saying "variability" with respect to the underlying asset, is constant. To most people the impact of this assumption is difficult to grasp, and its effect on the price of the option contract only minimally understood. All major derivatives models make similar assumptions, and those selling them do their best to downplay the effects.

Before I offend some very smart, devoted people, I will stop here and state that much of the basic work behind these models is sound on a theoretical basis, and that these models have on the whole, contributed greatly to theoretical as well as mainstream finance. (If you want to read more about this topic, Nick

Mocciolo has written a paper entitled

"The Cost Of Black Scholes" which is a fantastic summary of the issue outlined above.)

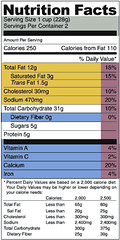

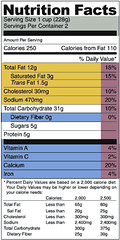

So what do derivatives pricing models and nutrition science have in common? Both take complex processes that occur "naturally" and reduce them to a series of rules that govern the interaction of their various components. In the case of derivatives models, price, volatility, time, and interest rates are the major parameters. In nutrition science, they are fats, carbohydrates, vitamins, minerals, proteins, antioxidants, and the like. This "reductionism" is necessary to gain understanding of a complex system as it is often necessary to break them down into more "digestible" components. The danger lies in over-simplification, and failure to see the entire system as greater than the sum of its parts. Ignoring the impact of the underlying assumptions made in derivatives pricing models can mislead investors about the risks of a particular instrument. And failing to understand the role of nutrients in a balanced diet would lead one to believe health can be obtained by taking a series of pills and dietary supplements. Neither are true, and acting based on these assumptions alone is dangerous. Sure, scurvy and rickets have been virtually eliminated, but some may argue that this has been offset by the rapid rise of obesity, and early-onset Type-II diabetes.

Giant food companies selling novel high-tech food products, and investment banks touting riskless returns, would like you to believe otherwise. They have used these simplistic reductions of complex processes to sell their ever-changing assortment of wares. And in both cases, the complexity and evolution of the current, in fashion, de facto model adds to consumer confusion.

A perfect example of this was William

Neuman's front page story of the New York Times business section last week, entitled

"For Your Health, Froot Loops." In an insulting and outright misleading effort by some of the biggest U.S. food companies, a new program entitled "Smart Choices" was launched, claiming to give consumers front-of-package guidelines for healthy eating. By using the rules of the current nutrition model,

Froot Loops made its way onto this list. How is this possible? Per the article:

Froot Loops qualifies for the label because it meets standards set by the Smart Choices Program for fiber and Vitamins A and C, and because it does not exceed limits on fat, sodium and sugar. It contains the maximum amount of sugar allowed under the program for cereals, 12 grams per serving, which in the case of Froot Loops is 41 percent of the product, measured by weight. That is more sugar than in many popular brands of cookies

I could write an entire post on this alone. A simple stroll through the middle aisles of the supermarket yields a cacophony of

counterintuitive, misleading, confusing nutrition "information." The packaging of almost every processed food item makes health claims such as "high in fiber," "hearth healthy," "low-fat," "low-sugar," "loaded with antioxidants" and so on. It's a simple formula: Convince consumers they have a new set of problems to solve, then sell them new, expensive solutions. How else could someone actually believe that a

cookie diet is a good idea? Same is, and was, true of financial derivatives. Just as bankers are screaming "inefficiency" in response to increased regulation and due diligence, and insurance companies do their best to obfuscate reform that will cut into their profits, the giant food companies use ever-changing tactics to prevent any kind of consistent food labeling or nutritional guidelines from being adopted.

The boring moral of this story is actually quite simple: stay diversified in your investments and your diet, and avoid anything that seems too good to be true. It probably is, and is just making you fatter, sicker, and someone in a corner office much, much richer.

This comment has been removed by a blog administrator.

ReplyDeleteThis comment has been removed by a blog administrator.

ReplyDelete